PrEP for Women: Claiming Risk and Recognizing Responsibility

This post features guest blogger, Lauren Suchman, PhD, and her study of gender dynamics in New York’s Ending the Epidemic campaign, with a specific focus on PrEP uptake among women. Dr. Suchman currently works as an Evaluation Director at the Institute for Global Health Sciences at UC San Francisco.

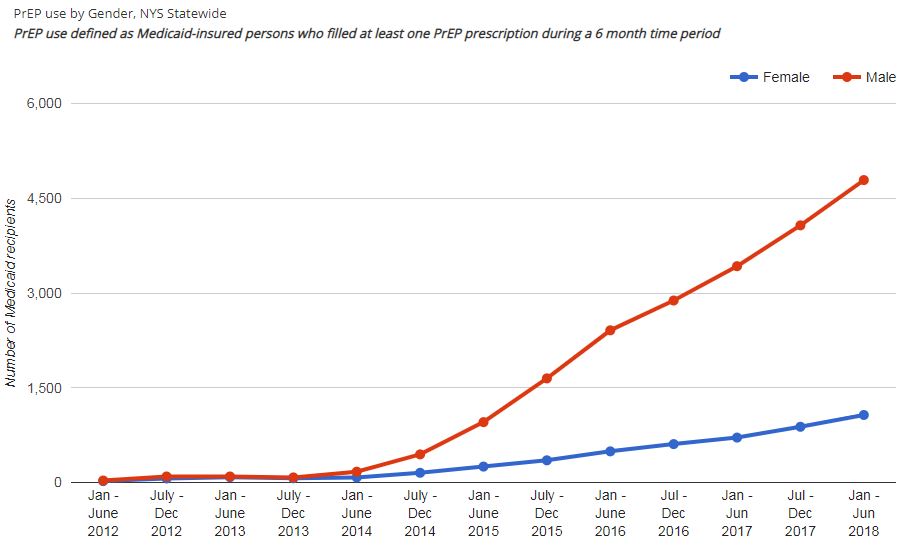

When filtered by sex,¹ data on PrEP use pulled from the ETE Dashboard indicates that 1,070 Medicaid-insured women had accessed PrEP in New York from January – June 2018, while this number was approximately 4,800 among men during the same time period. Although women in the U.S. are less likely to contract HIV than are men, this disparity in PrEP enrollment is no less striking. In response to such figures and to internal critiques, institutions operating within the ETE framework have started to focus more efforts on women; the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene’s “Living Sure” campaign provides a good example of this. However, gender differentials in PrEP uptake surely suggest a more complicated picture than a simple lack of “marketing” or promotion of PrEP to women. One recent study among women in the Bronx found that 45% of people seroconverting in the healthcare system during 2009-2014 (i.e., a negative HIV test followed-by a positive HIV test at a later date) were women, suggesting a need for improved HIV prevention options among this population. For those of us invested in reducing HIV incidence across New York State, how do we best interpret these numbers?

I believe the differential uptake of PrEP early in the push to end the epidemic was related to messaging around PrEP that built on gendered stereotypes of risk and responsibility. These messages reflect longstanding challenges, even among HIV/AIDS advocates and service providers, to accept that women take sexual risks, being just as “irresponsible” as men. Although this principle extends to women who use drugs, I believe it is particularly true when it comes to sexual risk and since most women, including substance users, get HIV through heterosexual contact, sexual risk among women seems most important for HIV prevention efforts to address. Throughout research I conducted in 2014-2015 examining gender and race dynamics in New York’s ETE campaign², I sat in on numerous meetings in which men participating joked or bragged about their sexual exploits, and in which sexual references pertaining to male genitalia and sexual acts between men were bandied around. This was especially true for men who have sex with men (MSM), and seemed to indicate acceptance of the idea that men are inherently sexual and will take sexual risks as a result. Indeed, this acceptance and comfort with sexuality has been one of the great achievements of AIDS activism. However, women in these settings rarely made such references. As one trans woman noted during a community event on PrEP in lower Manhattan: some groups aren’t allowed to brag about sex.

Further, in venues where women on PrEP (including one trans woman) spoke publicly about their experiences, they often appeared reluctant to discuss risky behavior and instead emphasized that they were being responsible by choosing to take PrEP. Dahlia³ provides a good example of the interplay between risk and responsibility for women trying to access PrEP. Speaking at a community event in upper Manhattan, Dahlia told the audience she had used PrEP to become pregnant with her HIV-positive husband and explained that she had done extensive research before approaching her doctor for a prescription. However, her doctor refused to prescribe PrEP, saying that she wouldn’t condone Dahlia’s “risky” behavior. Dahlia expressed her frustration, saying: I really was looking for [my doctor] to reduce and to minimize the risk to myself, and she kind of left me dangling with that. In this way, Dahlia stressed that she was trying to be responsible and take care of herself, but her doctor stood in the way.

Not long after Dahlia shared this story, a marketing campaign for PrEP spread across upper Manhattan. This campaign featured a black man sticking out his tongue to display a blue PrEP pill with the tagline “Swallow this” underneath. In meetings with the sponsors, I learned that the campaign was specifically meant to be “provocative” by sending a sexual message targeted at MSM of color and aligning this message with access to PrEP. For these men, sexual risk was an entry point to PrEP. Conversely, “responsible” women like Dahlia were considered too risky to be granted access.

Recognizing and legitimizing women’s right to risk therefore seems an important step in opening up access to PrEP. However, it also is important for those engaged in HIV prevention work to recognize that risk and responsibility are not mutually exclusive. Rather, women may be involved in “risky” behavior for a variety of reasons, many of which are shaped by power differentials due to their gender, race and/or class. In this context, a woman’s decision to start PrEP should be viewed as a responsible choice at the same time that her sexual choices may appear risky. Further, as one doctor who works largely with women of color in Brooklyn said to me, taking PrEP allows [women] this sense of control over their sexuality and ability to be intimate in a way that I think this population in particular deserves to have. And I think that has value in itself. Particularly for women who experience intersecting risks in addition to their gender, as with men, these risks should be acknowledged as a legitimate entry point to PrEP. PrEP in turn can enable these women to mitigate one of the many risks they face on a regular basis.

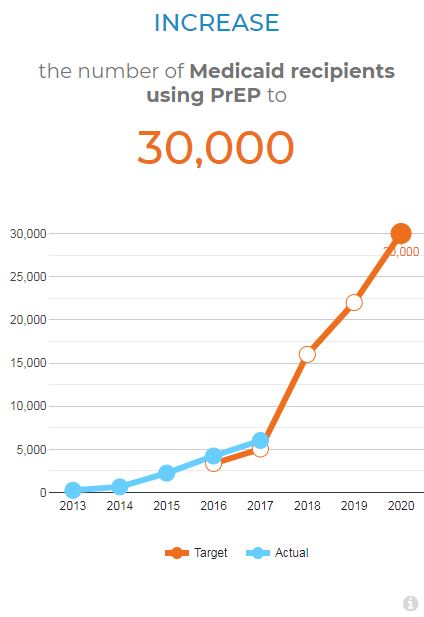

Since New York has set a target to increase the number of Medicaid recipients using PrEP to 30,000 by the end of 2020, I would challenge those using the Dashboard to read between the numbers as I have done above, and also to closely examine multiple data sources when thinking about where and how to allocate resources. We’ve explored the way gendered perceptions of risk and responsibility may be contributing to a disparity in PrEP access, as evidenced by the Dashboard’s PrEP use data. However, there may well be other ways in which we need to re-think the data to arrive at a more complete picture of the epidemic. The numbers alone won’t tell us the underlying drivers, and it will be up to all stakeholders to examine the available evidence and ask questions that may lead to new insights with the potential for impact. It is our responsibility to not only challenge our own preconceived notions about risk, but also our own preconceived notions about which numbers matter and why.

¹ The ETE Dashboard’s display of NYS Medicaid administrative billing data only includes “Female” and “Male” as filters under the category “Gender.” In this piece, I generally use “women” to refer to cisgendered women unless otherwise noted, since transgender women face a somewhat different set of issues related to HIV risk and PrEP access.

² While I was a graduate student in the Department of Anthropology at the CUNY Graduate Center, I conducted my dissertation research on Ending the Epidemic with a focus on the ways in which the campaign addressed or neglected gender, race, and class. This research was conducted from October 2014 – December 2015 when ETE was in the design and early implementation phase. It included interviews with 38 activists, academics, health service providers, government workers, and community members, as well as attendance at numerous meetings and events where the campaign was developed and implemented. I extend many thanks to current and former staff at the NYSDOH AIDS Institute who made this research possible. While this piece offers a critique of the ETE campaign, it is meant to be constructive and not at all a criticism of work that I found overall to be extremely impressive.

³ A pseudonym